The Science Behind the Meat Counter

March 11, 2025

By Chelsea Mumm

The next time you’re perusing the meat counter at the grocery store, take a second look at the coloring of each cut. An Iowa State University (ISU) student is working to figure out how lighting and packaging make a difference in meat appearance.

Stephanie Major is an ISU senior majoring in animal science and minoring in meat science. She grew up in southeastern Iowa and spent years in FFA. She came to ISU with plans to be a veterinarian, but during an internship her freshman year, she fainted during her first surgery observation.

Stephanie Major is an ISU senior majoring in animal science and minoring in meat science. She grew up in southeastern Iowa and spent years in FFA. She came to ISU with plans to be a veterinarian, but during an internship her freshman year, she fainted during her first surgery observation.

Instead, Major found inspiration at the ISU Meats Laboratory, where she worked her freshman year to gain experience in physiology and help with the lab’s meat harvest, fabrication and process development. The summer after her freshman year, Major stayed on for an internship to dive deeper into product development research.

“That’s when I really started getting interested in meat science,” Major says.

Shedding a Light on Meat Science

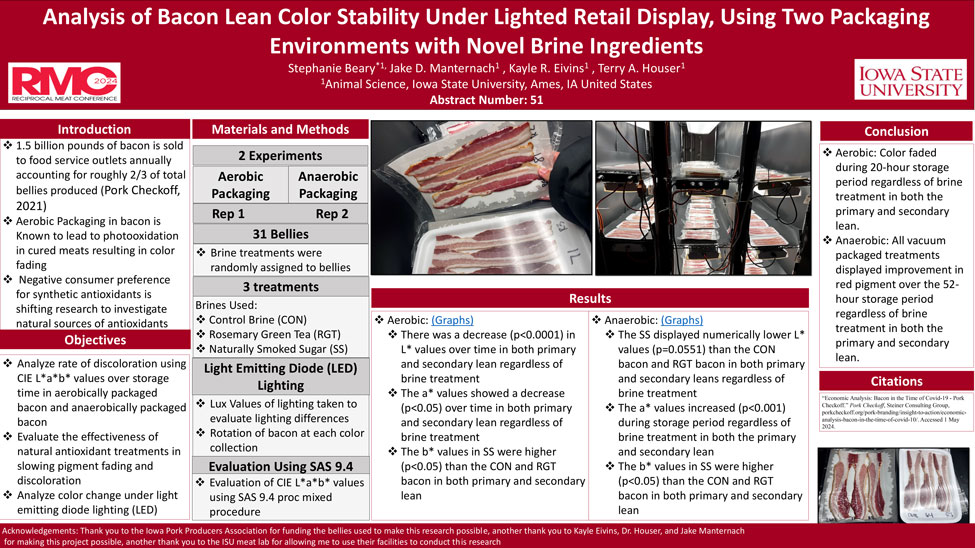

Major’s hard work culminated in a significant research project last summer, which she conducted alongside Terry Houser, associate professor of animal science. They looked at how retail lighting affects the color of bacon depending on the packaging type: aerobic overwrapped packaging (oxygenated) or anaerobic vacuum packaging (unoxygenated).

Over time, retail lighting causes photo-oxidation, which results in cured meat products graying or fading in color — which research has shown is not appealing to consumers.

“Bacon, in particular, is very susceptible to photo-oxidation,” Major says.

For 12 hours one day, Major worked in a cooler to monitor and register the color values of bacon in the two types of packaging to determine how aerobic overwrapped packaging affects the product differently from anaerobic vacuum packaging.

Bacon in the aerobic packaging began to fade in color within the first two hours of the experiment — demonstrating a dramatic change in color due to oxygen exposure. “We expected that would happen with aerobic packaging, but we didn’t realize how quickly it would happen, which surprised us,” Major says.

Bacon in anaerobic packaging, on the other hand, didn’t show much color change throughout the experiment. “When bacon doesn’t have exposure to oxygen, the meat cannot grab onto it to start the oxidation process,” Major says. “The opposite happened: The color stayed and, in fact, became redder and more pigmented.”

The reason behind this color shift is a question for another research study, Major says. Still, she hypothesizes that, based on other research, this could have occurred due to the mitochondria in the meat muscle still being active in its postmortem state. Therefore, the meat still took on oxygen and became more pigmented.

The Future of Meat Science

The Future of Meat Science

Major presented her work at the American Meat Science Association’s 2024 Reciprocal Meats Conference in Oklahoma City, where she received second place in the undergraduate research competition.

This is just the beginning for Major. “Consumers buy with their eyes,” she says, which is why there’s so much opportunity to research this topic. She wants to continue studying different packaging methods to find an approach that prevents photo-oxidation and preserves the meat’s appeal to consumers.

Following graduation in May 2025, Major has a couple of options: Attend graduate school to deepen her meat science studies or work in research and development.

“Any brands you see on store shelves, many of them have product development scientists assigned to specific products,” Major says. “I would love to work on the processing side, researching new products, conducting cost optimization studies or looking into ingredient substitutes.”